-

Posts

316 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

40

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Events

Articles

Blogs

Downloads

Community Map

Everything posted by V7#5b9

-

Andrew Wasson delivers the formal explanation. The first 5 minutes of the video provide the essence, the rest is just promotional stuff. The second video is interesting because it provides correct observations with regard to the standard tuning itself. However, I know nothing about Eric Blackmon, and I wouldn’t call his explanation a formal one. In my mind it does not qualify as the correct one, but it does serve as a good supplement. Apparently, YouTube does not allow embedding of this video, so you will have to use the link itself. https://youtu.be/5hc7OJqQYaA

-

I fully concur with the quote.

-

You still need to know the language, its grammar and vocabulary. Even when you speak off the cuff you repeat phrases you have used many times before. You seldom come up with something completely original. The speech may sound original, but not its components. The same is true of musical improvisation. If you listen to your favourite players really carefully, you will begin to hear similar licks repeating throughout their solos. This is not immediately obvious because these players manipulate their phrasing, rhythm and feel very well. After all, there are only 12 notes available. The only logical conclusion is that it is rhythm, phrasing, dynamics and articulation that make the difference. In a blues guitar solo where you may be playing only 5 or 6 different notes, it is even more evident. It’s very much a case of when and how you play, not what you play.

-

I’ve looked at Howard Morgen’s “Fingerboard Breakthrough” before. It’s an advanced approach, but so is Pat Martino’s “The Nature of Guitar” which I do have. One should not shy away from those approaches, but I think that the CAGED system should not be ignored, either. In fact, I think it’s a good idea to learn it first. You seem to be familiar with it, but your comment appears to imply its inferiority. Sorry if my interpretation is wrong. I just want to point out that the CAGED system is neither inferior nor superior. Such greats as Joe Pass, Tal Farlow and Barney Kessel endorsed it, and guess what! FundamentalChanges recently put out the book by Martin Taylor called Beyond Chord Melody. He never had what you might call a “formal” guitar lesson, but when he came across the CAGED system he realized that it was an accurate summation of how he views the guitar. Of course, you don’t have to use it just because so-and-so did or does. However, like it or not, name it CAGED or something else, that’s how the guitar’s fretboard is naturally laid out. Granted, the same may be said about other systems or approaches.

-

Griff has excellent blog entries. He even has a course on how to improvise blues solos. But, improvisation is more of a jazz domain. Head over to the Music Theory section and check out Improvising Over Chord Changes.

-

The following free resource material comes from Richie Zellon’s YouTube channel and his personal website. I think it will clear up any misconceptions one might still have about jazz improvisation. Even if you are not into jazz and improvisation, you may still find the information interesting and enlightening. Overview Of Special Considerations… I. We must have a proper understanding of all the chord-scale relationships within the harmonic progression we wish to improvise over. In brief, this means we must understand the function of each note in a scale in relationship to its offspring chords as well as the overall tonality at hand (e.g. major, minor, modal, etc). Remember all notes fit into one of 2 categories: harmonic tones and non-harmonic tones. To summarize: A. Harmonic Tones include all chord tones and upper extensions diatonic to the scale of the moment. B. Non-Harmonic Tones include any “avoid notes” diatonic to the scale of the moment and all non-diatonic chromatic notes. II. When we improvise a melodic line we are dealing with both a vertical and horizontal relationship to the current harmonic progression. The development of a good sounding phrase fully depends on an understanding of how these 2 aspects within your line interact with the moving chords. VERTICAL: When improvising over a given chord we should be primarily focused on outlining the most important harmonic tones of its mother scale. Thus our melodic line for most of the time takes on the shape of a gradually ascending and descending vertical structure also known as melodic contour. A good example of a vertical structure would be a 7th chord arpeggio. HORIZONTAL: A good example of horizontal movement takes place whenever we play a scale or any succession of notes in step-wise motion. Therefore, unless we are playing lines consisting exclusively of 3rds or larger intervals, there is an ongoing balance of horizontal and vertical movement in our melodies. However note that at the point of transition from one chord to another , our primary focus usually shifts from vertical to horizontal as we must connect both structures in a seamless linear fashion. This is what is referred to as voice leading and is best accomplished by resolving to the closest guide tone (ie. 3rd or 7th) of the new chord. Consequently the smoothest transitions employ step-wise motion. The following videos constitute a four-part tutorial on how to use “The Jazz Guitarists Signature Series” to expand your improvisational vocabulary. You will undoubtedly see that improvisation goes beyond the simple memorization of licks and the plug-and-play idea. There is even an element of spontaneity in it, but for the most part, it comes from what you learn in the practice room. If you had the patience and tenacity to come this far in this post, I’ll throw at you one more video as an example of phrases (licks) deconstruction and usage. All this material is available for free, and I’m sure it will complement any improvisation study materials you may already have, like the ones recommended by Steve. If however, you find your materials insufficient in some areas, Richie has an excellent, college level, two-volume series on improvisation.

-

??? … and in the spirit of blues, they are all dominant 7th chords.

-

The 12-bar blues form serves as a springboard for “Day Tripper.” The verses begin with two four-bar phrases that follow the typical poetic, harmonic, and instrumental guidelines of the blues. Actually, I can hear the common call and response pattern of blues phrasing in the melody, while the ostinato riff opens and unifies the whole song. The third phrase is extended to eight bars, and in my mind serves as a punch line.

-

Call and Response is a common pattern of blues phrasing. This concept is not only present in vocal blues, but also in the development of many instrumental blues solos. So you can definitely have a conversation with yourself in your own improvisation. It doesn’t have to be in the context of a 12-bar blues, but some sort of symmetrical form is helpful. Many tunes have four- or eight-bar sections that can easily be divided into one-, two-, or four-bar chunks for the purpose of call and response. One way to do this on a 12-bar blues form is to treat each third of it as a small three-phrase segment. That is, a short, rhythmically similar phrase is played in each of the first two bars, while the next two bars contain a longer line that seems to answer the first two. This repeats for both of the remaining four-bar segments. Another device within the framework of call and response is to jump between higher and lower registers. This range jumping idea can be applied to a tune with more chord changes and a swinging rhythm. It’s a good effect to use sparingly. Call and response was a prominent feature of the musical environment that helped to shape the jazz style and continues to appear throughout the tradition in compositions and in solo statements. To get a better sense of this concept follow the link: Five Types of Call and Response Phrases.

-

I have just upgraded to the latest 2018 BIAB version. So far I’ve been using it mainly for the etudes in Richie Zellon’s BGIS course. I find it a very versatile tool. The RealTracks are outstanding, and so are the backing tracks you can quickly and easily create for yourself. However, the versatility goes way beyond simple backing tracks. The $130 basic package is probably more than enough for most of us. I think BIAB has become one of those must-have tools for some time now.

-

Let’s not forget that jazz evolved from blues and not the other way around. You can improve your traditional blues playing without knowing anything about jazz. It’s more about the blues scale, phrasing, using bends, hammer-ons and pull-offs. On the other hand, if you want to enhance your blues playing, you will move from Traditional Blues to Jazz Blues to Minor Blues to Bird Blues.

-

More and more books tend to use both regular notation and tab. But, there is one resource that goes a step further. It’s called Bebop Guitar Improv Series. The study includes a notational system occasionally referred to as intervallic script. It is in no way meant to be a substitute for traditional music notation. The main purpose of intervallic script is to serve as a system of staff-less notation, to analyze and memorize melodic phrases in numerical formulas that can easily be recalled, transposed and applied to any key as improvisational vocabulary. In addition it has proven to be an invaluable system in training the mind to visualize the components of a scale and their melodic function in relationship to a given chord. This is a crucial resource when improvising, due to the fact that it is much more practical to think in transposable numerical patterns rather than actual notes. Intervallic script has its limitations, of course, therefore conventional notation and tablature are used throughout the study as well. If you are not a proficient reader, your best next option is to use both the regular notation and tab.

-

@Triple-o Take a look at the musical analysis of “Autumn Leaves” provided on the following PAGE. When you get to the page, you may have to click on the “Music and Lyrics Analysis” in the left column to see the result in the middle column. The original key is G major/E Minor, and the form is A-A-B-C. So, the first 16 bars are the A-A section. The next 8 bars are the B or Bridge section, and the last 8 bars are the C section. When the sections are melodically different, they can be assigned different letters: A, B, C or even D. Now, I don’t know about “breakdown bridge”, but as far as I’m concerned when you add the lyrics (and I do have “Autumn Leaves” sheet music with lyrics version) the B section starts with “Since you …” as you point out, and the C section starts with “But I …” I hope that makes sense to you.

-

Total improvisation is a myth. The ideal in the art of improvisation is to pre-hear lines in your head and then execute them on your instrument. Some players would like you to believe that all of their ideas are completely spontaneous. Many devices and concepts go into creating a good improvised solo. Scales, modes, arpeggios, melodic patterns and licks all play a certain part, along with moments of spontaneity and true inspiration. However, to a large extent, improvisation is really the “creative reorganization” of things you already know.

-

You’re welcome @Triple-o. The Gold options were my choice. My Vol.1 & Vol.2 memberships have expired, so I no longer have access to the forum over there. If you decide to enroll, let me know via PM here and I’ll send you a little hint on how you can get the most bang for your buck. I’ll gladly help you out in answering any questions you may have now, or in the future re: BGIS.

-

That’s pretty much it, but more specifically, you need to be familiar with three elements. 1 Chords & Rhythms Some common blues chord shapes. How the 12 bar blues form works. How to find the I, IV, and V chords in any key and apply them to the 12 bar form. At least one common blues strumming pattern or rhythm. How to start your blues song. How to end your blues song. 2 Soloing What note to start your solo on. What beat to start your solo on. Pentatonic and blues forms. When to use lead techniques (bends, hammer-ons, pull-offs). Licks (phrases). 3 Putting The Pieces Together Assembling your Intro, Rhythm, Solo and Ending. Using licks (phrases) or single notes as fills between vocal lines.

-

@Triple-o I was going to respond, but you keep changing your post and I don’t really know what to focus on. Are you just making a statement now, or do you want some feedback on specific questions? It appears you are looking for the deep understanding of melody and harmony. Well, I’ve mentioned Richie Zellon’s Bebop Guitar Improv Series more than once on this forum, but nobody seems to be really interested at this point. I don’t think you will find any other resource that matches the depth of instruction of the series. Will it tell you how to translate “Once upon a time” into a musical line? Not exactly, after all that type of translation depends on the interpreter, but it probably will answer more questions than you can come up with. If you want to translate specific words into music, Pat Martino’s Alphabet Junction might be your answer.

-

How do I improve my ear and improvisation skills?

V7#5b9 replied to Magnit's topic in Guitar Playing & Technique

@Magnit “Maybe delve into arpeggios?” Yes, absolutely. Arpeggios are the target notes all approach notes resolve to. It doesn’t matter whether the chords you are playing over, are inside or outside the key. “Learn loads of licks by heart?” Yes, absolutely. The phrases you learn become your musical vocabulary, as long as you understand their anatomy and how to use them. Here is a short list of courses for you to consider: Chord By Chord Blues Soloing How To Improvise Blues Solos Bebop Guitar Improv Series As for improving your ear, check out Jazz Guitarist’s Guide To Ear Training. -

... with Paul McCartney.

-

Session 17 - Going Beyond the First Position

V7#5b9 replied to NeilES335's topic in Gibson's Learn & Master Guitar

First of all, do not put any time limit, or compare your progress with somebody else’s. Everyone is different and it takes as long as it does for you to see significant, positive results. Don’t try, just do it and do it consistently. Trial approach is your biggest enemy. Secondly, I don’t think Steve would recommend this method, if it didn’t work. Any method will work eventually if you stick with it. So, to answer your question directly, I personally don’t know of anyone using this method and succeeding. However, I do assume the majority of students here do use this method and succeed. All I can tell you is that my approach to learning the notes of the fretboard was different from the very beginning. I used a couple of methods. One was to just go up and down each string between the nut and the 12th fret, naming the notes using sharps for accidentals when ascending, and flats for accidentals when descending. The other method involved “Five Root Shapes.” Beyond the 12th fret everything repeats. So, I know all the notes of the fretboard and how they relate to the musical staff, but I tend to view it in terms of three four-fret zones. The main reason for knowing the notes is to be able to read music, but also to know where to play the chords, or start scale/arpeggio patterns which I view in terms of easily transposable intervals, or scale degrees. When we play we can’t think fast enough in terms of notes or even intervals or scale/arpeggio degrees. The fingers have to do it automatically for us. But, when we learn and practice our scale/arpeggio patterns, riffs, licks or phrases, we need to be aware of intervals or scale degrees so we know where the chord as well as diatonic and chromatic approach tones are. Intervallic approach allows for much easier transposition of these elements to other keys as the patterns usually remain intact (sometimes they have to be adjusted), whereas the notes change from key to key. -

Session 17 - Going Beyond the First Position

V7#5b9 replied to NeilES335's topic in Gibson's Learn & Master Guitar

The “Three-Notes-On-A-String” scales are navigational patterns, just like the pentatonic forms. They should be learned in terms of intervals, which are easily transposable to any key, rather than notes in those patterns. The notes of the fretboard in any given tuning don’t change, but their function may change depending on the context. So, learning the notes of the fretboard using scale patterns will work eventually, but it may cause more confusion in the beginning and delay the progress. I suggest you pick a method that directly deals with the layout of notes on the guitar fretboard and how they relate to the musical staff. -

Free Jazz Chords Supplemental Resource

V7#5b9 replied to V7#5b9's topic in Jazz Chords Fretboard Workouts

So, here’s the second video with some “Butter Notes” for comping.- 12 replies

-

- 1

-

-

- string sets

- jazz chords construction

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with:

-

@knightgodinmontreal If you really want to learn all about jazz guitar and the art of jazz improvisation as applied to the guitar, consider Bebop Guitar Improv Series!

-

-

Free Jazz Chords Supplemental Resource

V7#5b9 replied to V7#5b9's topic in Jazz Chords Fretboard Workouts

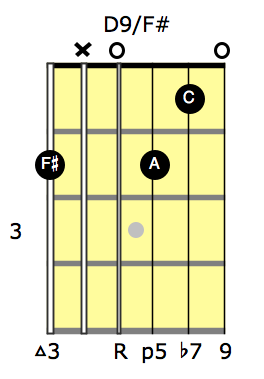

Comping seems a fitting topic for this thread so I thought I’d put it here. Despite promotional aspect and informality of Richie’s videos, they cover important concepts with a fair bit of depth and you can get a lot out of them. Below the video and for your convenience, I provided a little transcript of the chord types Richie talks about and what you can do with them. Richie promises a follow-up vid as well. Major 7 Chords (1-3-5-7) When a major 7 is over the I of the key you can add the 9 or the 13. When it’s over the IV, it’s a Lydian chord which allows for all it’s upper extensions… 9, #11 and 13. You get to choose. Dominant 7 Chords (1-3-5-b7) This is going to vary widely as far as the extensions go. Usually, although not always, if it resolves a perfect 5th down to a major chord it can use the 9 or the 13. However, if it resolves a perfect 5th down to a minor chord, it will use a b9 or #9 and if you like a #11. A b13 can also replace the 5th. This becomes what is known as an Altered Dominant. Minor 7 Chords (1-b3-5-b7) Almost all minor chords can use a 9th and the 11th, however avoid the 9th if it is a III minor chord. Minor 7b5 Chords (1-b3-b5-b7) also known as Half-diminished chord. For most instances you are safe using the 11th and the b13. Use the 9th only when the I is a Imin6 or Imin-maj7 chord. Diminished 7 Chords (1-b3-b5-bb7) Augmented 7 Chords (1-3-#5-b7) This chord sometimes implies the more complex altered chord. The altered chord can also be viewed as an alternative for an augmented dominant 7th because it has all the same basic tones only that the upper extensions are all altered, that is if you use a 9th it should be a b9 or #9, if you use an 11th it should be a #11. The b13 of course is a #5 which should already be a part of the fundamental 7th chord. Altered Dominant 7th Chords (1-3-b7 / b9, #9, #11, b13) Another instance that usually implies the use of the altered dominant is when you see a 7b9 or 7#9 chord. Dominant 7 Suspended 4 Chords (1-4-5-b7) Here you can safely add the 9th and 13th. Slash Chords (D/C = D triad with a C in the bass) are a way of sometimes simplifying the spelling of an inversion wanted for a chord with specific extensions. Usually, the first portion is an upper extension triad. D/C is made up of: A = 13 F# = #11 D = 9 C = 1 In relation to the C, D is the 9th, F# is the #11, and A is the 13. So, if you know your harmony, you will recognize it as a Lydian or Lydian b7 chord. Another common example would be: F/G C = sus4 A = 9 F = b7 G = 1 In relation to the G bass note the F is the dominant 7th, the A is the 9th, and the C is the sus4 or the 11th depending on the context.- 12 replies

-

- 1

-

-

- string sets

- jazz chords construction

-

(and 1 more)

Tagged with: